David Lanier: The Making of American Bird-Dog Artist

I set out quail hunting with David Lanier at Carr Farms in the plantation belt around his hometown of Albany, Georgia. He’s an affable guy with your average mid-50s paunch and a friendly clean-shaven face shaded by the brim of a blaze ball cap. The brush pants, frayed at the hems, bunched up at the buckled wingshooter boots scuffed and rough, his forest-green hunting shirt nicely ironed and the pouches of his vest swollen with gear (he always hunts with a camera).

The birds flushed in singles and doubles from the winter crop fields and he deftly shouldered the old Browning to down his share of quarry. Watch him in the field and you’d think he’s just another capable quail hunter. But Mr. Lanier is one of the best bird-dog painters walking the planet. As a sporting artist, he sees our natural world of birds and dogs, fields and forests, mules and horses differently than you and me; he also occupies another dimension comprised of value patterns, forms, structures, perspective, color palettes and shadows.

David Lanier hunting bobwhite quail at Carr Farms in Albany, Georgia.

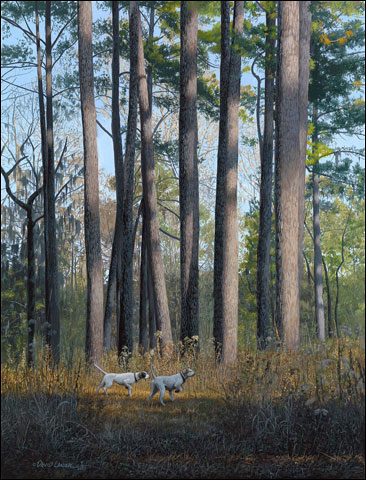

“I spend as much time in the field as I can,” he said. “I want to keep that ring of truth. The dogs I like to paint are dirty and rugged – how they look at the end of the season after running for a couple of months. They’re not cover models, I don’t glamorize them. I want to portray the truth of the dog. I want my paintings to capture their individuality.”

His photo-realistic acrylics of bird dogs have earned him widespread acclaim and funded preservation of the lands we hunt.

By his own reckoning, since the early 1990s, prints of his original painting have raised $5 to $10 million dollars in auctions and sales for conservation organizations such as the Wild Turkey Foundation, Ducks Unlimited and Quail Unlimited.

Lives to Hunt

“The greatest satisfaction I get is working with the conservation groups,” he said.

Mr. Lanier’s sporting art has appeared on several state of Georgia duck stamps and garnered magazine covers including Gray’s Sporting Journal and Quail Unlimited. He keeps a full slate of dog portrait commissions throughout the U.S., although he always schedules time to build portfolios for the three major art shows he attends each year.

A few weeks after our quail hunt, I visited his rustic studio behind the Lanier’s modest suburban house in Albany. Set far back from the street, the studio of about 1,000 square feet was originally a mechanic’s garage. Paneled with cedar planks, his easel is situated near sliding glass doors that let in natural light.

David Lanier in his studio.

“I love what I do,” he said. “I could paint fur and grass all day and love every bit of it. I never intended to be a dog painter. I painted landscapes and birds, but people really liked the dogs.”

His inspiration arises from an all-American boyhood in Albany.

“I am fortunate to have parents that introduced me to the outdoors at an early age,” Mr. Lanier said.

He grew up hunting and fishing with his father, who he described as an outdoorsman. His father would take Mr. Lanier and his brother to their aunt’s property, some 1,000 acres, where they pitched a tent, honed their survival and trapping skills while shooting rabbits, doves and quail. He recalled his first shotgun was a single-shot .410. The adventures shaped his observational skills about the natural world.

Deep South Pointers

“There’s no place else I’d rather live,” he explained. “Most of the scenes I paint are twenty minutes from my house. We have quail plantations on three sides of us. What more could you ask for?”

But Mr. Lanier almost spent the rest of his professional days creating illustrations for religious publishing houses and local businesses until an injury changed the course of his life.

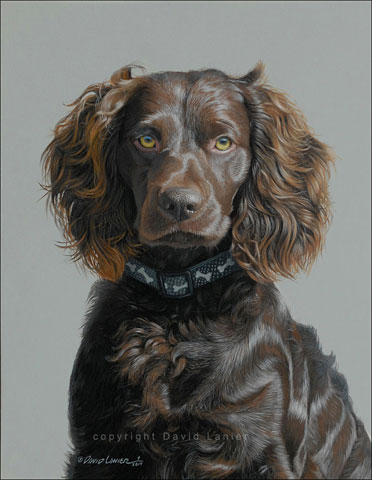

Parker the Boykin Spaniel

As a kid, he enjoyed coloring books and over the years realized that he was talented at drawing. By the time he reached Albany High School he was taking art lessons there. He also pitched southpaw for the school baseball team and Little League.

“I was pretty much pitching non-stop,” he said.

During that time, though, an art teacher showed him a documentary about the American painter, Andrew Wyeth. The film got him thinking about a professional art career.

“I thought it would be good to work at home, not tied down to an office, and watch our kids grow up,” he recalled.

Springers and Purdeys

A relentless baseball program eventually damaged his shoulder. He was forced to take a break between the freshman and sophomore years at Troy University in Troy, Alabama for corrective surgery – ending his pitching career. Facing a crossroads, he transferred to the acclaimed Ringling College of Art and Design in Sarasota, Florida in 1982, where he graduated three years later.

“I studied advertising and illustration there,” Mr. Lanier said. “At the time I thought that to make a living at art you had to do commercial art. I didn’t know anything about sporting art.”

Over the ensuing six years, he built a successful commercial art business by specializing in drawings. Come 1990, though, he encountered a surprise revelation. A friend suggested he visit the Southeastern Wildlife Exhibition (SEWE) held in Charleston, South Carolina.

Yellow Lab

“There were about 150 of the best wildlife artists in the world there,” he recalled. “We weren’t there for more than ten minutes when I said to my wife ‘I’d rather do this.’ She said she would support me.”

His wife, Cathy, decided to teach elementary school for one more year, helping provide him with the time to build a portfolio of sporting art for the show circuit.

Returning home, he immediately contacted his publishing and advertising clients and told them he was leaving the business immediately.

“I decided to devote myself exclusively to sporting art,” he explained.

Hank with Quail

Financially, the move was a sacrifice, considering they had a young daughter. Despite the risk, Mr. Lanier felt he was heeding a higher calling.

He writes of the turning point to sporting art on his web site: “The decision to paint wildlife was an easy one. I believe it is my purpose in life to show others the beauty that surrounds us and, hopefully, point people to the Divine Creator whose work I can only imitate. We are so blessed to live on such a diverse planet where the natural world is so alluring. How mundane it would be if our geography resembled that of the moon or Mars. I choose to believe that God created this world to keep us in a constant state of wonder and amazement, and it is because of that fascination that I paint the scenes and animals that I do.”

Under Tall Pines

Mr. Lanier promised himself that within three years of the transition he would qualify as a SEWE exhibitor (he succeeded).

“So much of my commercial illustration work was in black and white,” he said. “I had to teach myself color painting, to find my voice in that.”

Mr. Lanier’s earliest works of game birds and hunting dogs were picked up by Ducks Unlimited and Quail Unlimited for fund raising. In effect, the groups purchase the print rights to the original paintings. Unfortunately, he would find himself with hundreds of extra prints. He brought them to the local frame shop that sold them for three years, then realized that he could make more money selling them himself, assisted by a professional sales person. The business model was working for him so he expanded the sales team.

David Lanier with his wife Cathy in their Plantation Gallery in Albany, Georgia.

The next logical step would be to open his own frame shop and gallery devoted to his own art called the Plantation Gallery. That happened 22 years ago. Then in January 2018, the Laniers opened a brand new frame shop and gallery in Albany that keeps on hand about 50 of his prints and original paintings.

“People love their dogs and through the gift of art I have the chance to make them happy,” he said. “Sometimes I’d unveil a painting and the person would cry because it was of a dog they lost and they’d say to me ‘Thank you very much.’ That’s a part of the business I never anticipated.”

Irwin Greenstein is the publisher of Shotgun Life. You can reach him at contact@shotgunlife.com.

Useful resources:

The Plantation Gallery Facebook page

Irwin Greenstein is Publisher of Shotgun Life. Please send your comments to letters@shotgunlife.com.

Comments