The Browning Ernest Hemingway Left Behind in Paris

There were at least two Browning Superposeds in Ernest Hemingway’s life. One of them was a very early model that may have come indirectly from Val Browning, the son of John Browning, the genius who designed the gun. However, neither its serial number nor its fate are yet known. However, the second B25 − as the Superposed is still known in Europe − is a standard–grade 12-gauge field gun, Serial No. 19532, with double triggers and 28-inch barrels (both choked Full) with a ventilated rib. It was made in Belgium and sold to Master Mart, a retailer in Fremont, Nebraska, on 26 October 1949 for $195.20. After that, we don’t know how, when or where Ernest Hemingway acquired the gun, whether new or second-hand, or what he accomplished with it, but we know where it is today and how it got there.

From 1956 on, Browning No. 19532 belonged to a man named Claude Decobert, who joined the fabled Hôtel Ritz, in Paris, as a 16-year-old bellboy just after the Second World War. Decobert quickly was promoted to barman, a position he then held for 40 years, until Mohamed al-Fayed bought the hotel in 1987. Ernest Hemingway and bartenders usually got on famously, but in this case the relationship grew far beyond “I’ll have another!” and “Coming right up, Mr. Hemingway, sir.”

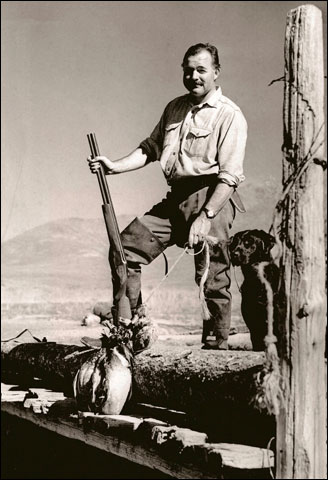

Idaho, fall 1939—a shirtsleeves day of duck hunting on Silver Creek. EH is just 40 years old but already a celebrated author. His gun is a first-generation example of the groundbreaking new over/under from Browning. EH said he’d won it from an American named Ben Gallagher in a live-bird tournament in France. Since it’s an early Superposed, and since Gallagher was close to Val Browning, whose father designed the Superposed, it’s possible the prize gun was donated by Browning himself. By 1958, when EH returned to Idaho after a 10-year absence, this gun had disappeared. Lloyd Arnold/John F. Kennedy Library

Hemingway knew and loved Paris, visited the city often, and frequently stayed − lived, in fact − at the Ritz, sometimes for many weeks. Hemingway’s legendary, if not mythic, “liberation” of Paris, on 25 August 1944, ended when he and his band of French and American irregulars sped down the Champs Élysées in their jeeps, turned left up to the grand old hotel, and Hemingway ran in to order martinis and lodging for everyone.

Hemingway was in his 50s during Decobert’s early tenure at the Ritz, and increasingly aware that his best days were behind him. Hemingway “used to come into the bar regularly, mostly to be alone,” Decobert told the literary journal Frank in 1998. But “he never drank a lot in the bar and we never saw him drunk. Everyone thinks of him as a big and brash man, but with me he was always friendly, even tender.” Especially as he aged, Hemingway was at his best with people to whom he had nothing to prove, and the younger they were, the more comfortably and genuinely he could play his “Papa” role as a mentor.

Conversations that began at the hotel’s Little Bar − Hemingway was confident in Parisian French; Decobert knew just enough English to take cocktail orders − about travel, hunting, boxing, fishing and life in general sometimes continued elsewhere when Claude went off duty. (In addition to being a celebrated hotelier, Charles Ritz was also a renowned angler, and he taught young “Claudie” to fly-fish. To Papa Hemingway, Ritz was “Charlie.” The Little Bar was re-named the Hemingway Bar.) One day, Decobert said, Hemingway showed him 12 guns that he had in his room, and asked: “Claude, if you could have one of these, which would you pick?” Decobert, who was neither a shooter nor a hunter, hesitated and then chose “the canardiėre, a long rifle [sic] used specially for shooting wild ducks.”

Browning 12-gauge Superposed No. 19532, the “canardiėre” (duck gun) that Ernest Hemingway presented to young Claude Decobert at the Hôtel Ritz, Paris, in 1956. Its serial number dates the gun’s manufacture to 1949. Anne Decobert

Before Hemingway checked out of the Ritz that time, Decobert said, he returned to the bar and handed over the gun − Browning No. 19532 − in a brown case.

“This is for you,” Hemingway told him.

“But, Claude, there are conditions. This is a symbol of the battles you’ll face in your life. Because as you grow older you’ll have to fight for your life. All the time.

“Claude, never give it away or sell it. You should save it and preserve it as something precious. Each time you have a problem, a worry, anything difficult that needs to be resolved, you’ll have to do battle. And this gun will be the symbol of your personal war.”

The short letter that Decobert received with the gun (signed “from his old friend and fellow hunter Ernest Hemingway, Fait à Paris, Lu et approuvé” − written in Paris, read and approved) is dated 9 December 1956. Two weeks earlier, when Hemingway had arrived from Madrid, the Ritz staff had presented to him two trunks full of his notebooks that had been stored at the hotel since the 1920s.

Decobert told Frank that Hemingway later took him to Chalo, the Paris gunshop, to have the Browning’s stock shortened and the trigger pull lightened, and that half a dozen times he shot boxed pigeons with Hemingway at Issy-les-Molineaux, on the southwestern edge of Paris, near the old aerodrome where the city heliport is today and where the 1924 Olympic trap-shooting events were held. Decobert recalled stopping at the Hôtel George V to pick up Gary Cooper to shoot with them, but “Mr. Cooper wasn’t all that much fun. He kept to himself and didn’t say too much.”

Faithful to his old friend’s instructions, Claude Decobert has never sold or given away the Browning. When, with the help of another Ritz barman − Alain Duquesnes, who in turn had been mentored by Claude − we tracked him down, in 2015, M. Decobert was genial and helpful. Through his daughter Anne he sent us photographs of No. 19532. The gun continues to be a symbol for him of necessary struggles, of the sort of determination that allowed Santiago to capture the giant marlin in The Old Man and the Sea, which earned Hemingway a Pulitzer Prize in 1953 and contributed to his Nobel Prize for Literature a year later. It’s likely that Hemingway was working on the book at the Ritz while his friendship with Claude was forming.

Decobert ended his Frank interview with Hemingway’s suicide: “When he died in 1961, I wasn’t at all surprised. I knew why he ended up the way he did, by removing himself from life.

“He’d come into the bar and we’d talk, but it wasn’t the same. The last two years of his life there was no more fight. And when the fight was over there was no more life. I remember the last time he came in to say goodbye. There was nothing at all left. He said he had no more creative ideas in him. I understood by looking at him. I knew that his time was over. I knew that he was very sick. He had become a common man and he didn’t want to be a common man.”

From the revised, expanded second edition of “Hemingway’s Guns,” Lyons Press, 2016, by Silvio Calabi, Steve Helsley & Roger Sanger. The book is available on Amazon at https://goo.gl/g9l51a

A chapter from the first edition of Hemingway’s Guns titled “The Winchester Model 21 Shotguns” was previously published on Shotgun Life at http://bit.ly/2m4GPoU

Irwin Greenstein is Publisher of Shotgun Life. Please send your comments to letters@shotgunlife.com.

Comments