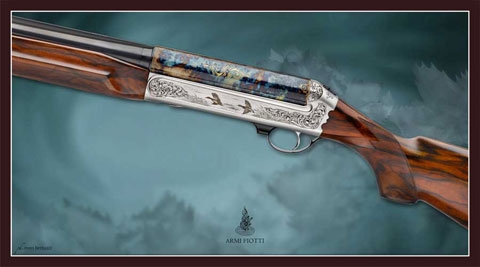

When we think of bird hunting, we instantly go to a sacred place that exists in our hearts – a sacred covert we protect. We dream of finding that place again and want to know it will still be there long after we are gone. As a group, we engage in friendly debates about the dogs, guns and game we prefer. We share our stories, but it’s that moment we find alone in the field that we think about at the end of the day, in a comfortable chair. The birds we hunt are worth finding for the first time, worth fighting for and worth remembering.